by Leah Veress

Getting up and at ‘em in warmer weather.

When the weather warms and the Bozone defrosts, odds are you’re itching to pull out your hiking boots, climbing gear, mountain bike, or fishing rod—but why not broaden your horizons, beat the crowds, and dive into some new, less mainstream outdoor activities this summer? Here are a few ideas to get you started.

Hunting & Gathering

Kill two birds with one stone, avoid the masses, and get in touch with your long-repressed primal side by finding your own food. If you’re interested in cutting your teeth as a hunter, don’t just twiddle your thumbs ’til big-game season comes around. Instead, learn how to hunt, clean, and cook wild game by pursuing smaller critters like squirrels and rabbits—species whose seasons are year-round. Head onto some public land—off-trail to avoid startling hikers—with a .22 rifle or 20-gauge shotgun and get to it. Come fall, you’ll be ready for the bigger fellers.

If the idea of harvesting an animal makes you queasy, fret not. The mountains of southwest Montana host an abundance of huckleberries, strawberries, raspberries, and edible mushrooms. Grab a basket and head to the highlands. We can’t give away our spots, but with some research and time spent in the backcountry, you’re sure to discover your own crop. Once you have your foraging skills dialed, you can begin pursuing fungi. Spring is morel season, and late summer brings a bountiful chanterelle crop. But be sure to bring an ID book or a knowledgeable buddy along—both species have poisonous lookalikes.

Slacklining

First pioneered by Yosemite’s rock-climbing community, slacklining has snowballed in popularity among various alcoves of the outdoor community. The practice—walking across a length of one- or two-inch nylon webbing suspended between two anchor points—claims a host of benefits, like improving balance and inducing meditative states. All you need to get started are two trees and a line. Start above soft ground in your back yard or a local park. Once you’ve got the hang of things, you can move to highlining or water-lining.

Wildlife Watching

Snag your binos, ID books (or download an app like Merlin or Seek), a snack, a good hat, and get ready to glass some wildlife. You can head into Yellowstone Park—a quick hour-and-a-half drive from the Bozone—or into any of the surrounding mountain ranges. Just be sure to respect private-property boundaries and give wildlife adequate space, lest you become a battering ram or dinner. If birding is more your speed, you’re in luck. With the Indreland Audubon Wetland Preserve right on the edge of town, you won’t have to travel far to spot your favorite feathery friends.

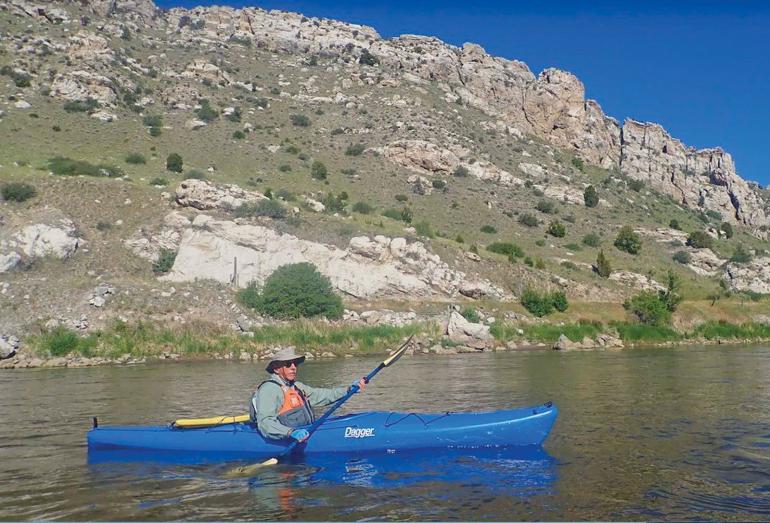

While still water is often cast as the ugly cousin of whitewater in southwest Montana, it shouldn’t be overlooked. If you’re looking for a relaxing day, load up your canoe, kayak, or paddleboard and hit the lake. Some good options are Hebgen, Quake, or Ennis lakes. Bring a lunch and get off the water to beat the afternoon winds, or put in early and end your paddle before they pick up. You can also cast a line from your craft and score some dinner if that’s your thing.

Cliff & Bridge Jumping

For the adrenaline junkies among us—and Tom Petty—few things beat that weightless, heart-in-your-throat feeling of free-falling. With spots like Williams Bridge by Three Forks and the ragged cliffs above the Ennis Lake dam, it isn’t hard to come across opportunities to catch some air and leap into the water. Always test the water’s depth before jumping—either by visually inspecting the area for obstacles, swimming to the bottom with goggles, or dropping a weighted object like a rock or anchor.

There’s really no wrong way to enjoy a Montana summer so long as you’re outside. So grab a buddy, a mentor, or go at it alone and meet some new friends on the water, in the field, or on a mountain.